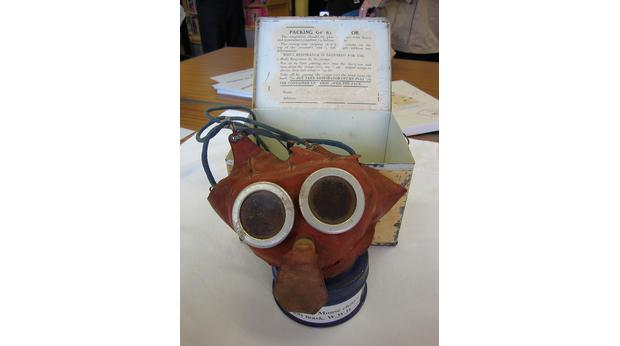

Here lays an exact model of the gas mask provided by the British Home Office in 1938. This specific respirator was produced to protect children from the age of eighteen months to four years. The mask was commonly known as the ‘Mickey Mouse’ gas mask, taken from the American version interestingly designed by Walt Disney. Disney’s aim was to make it more user-friendly for children, it was also his idea to go to the extent of having the ‘Mickey Mouse’ face printed on the American version. Its function was analogous to the way a cigarette filter reduces the amount of toxins a person inhales when smoking- see more here. Approximately forty million gas masks were produced for the British population; John Welshman states that the provision of these gas masks in 1938 was also more than adequate (Welshman, 2010, p. 31).

The British Home Office refused to take the risk regarding the potential for chemical warfare. Titmuss wrote in 1950 that during the 5 years preceding the war it was believed the Home Office was ahead of other European countries, in expectation of, and in preparation against gas warfare (Tittmuss, 1950, p. 6). The significance of this point comes from the fact that almost every child in Britain would have been allocated a gas mask- and every single one of them would of had their own individual views towards it. Before trying to determine how this affected each child it is important to remember that young children are politically less informed than adults, as a result they do not understand or comprehend the ‘enemy’ concept the way their parents do (Venken, Roger, 2015, p.204). Because of this, the new device could have brought a sense of bewilderment for children, sheer trepidation for others and for some the new device will have even brought excitement. However, for Derek Dawes, a young boy from Plymouth the memories of the gas mask were far from pleasant.

Here is his account from the BBC oral histories of what he remembers from school “I remember we had gas practice at school one day, we were thrown into a lorry that contained tear gas. I remember the part of the mask you looked out of steamed up and you could not talk- I hated it” This would have undoubtedly been a daunting prospect for a young child, furthermore this example shows how children were not wrapped in cotton wool when it came to the unforgiving requirements of war. It could be argued that Dawes’ recollection of an event in 1939 told in 2003 may have inaccuracies. This is an obstacle that many historians often encounter when trying to gauge what childhood was like during the war. Moreover, retrospective accounts make it harder to accurately measure how objects such as the gas mask influenced the psychological state of children. Additionally, negative firsthand accounts of the war are not extensively accessible to the modern historian, this further limits our perspective on social matters. Waugh argues that this is because much historical evidence available is biased due to the fact the government didn’t want to affect the morale of the country. Nevertheless, what the gas mask opens up is the discussion of evacuee children and the more general topic regarding life as a child in Britain during the war.

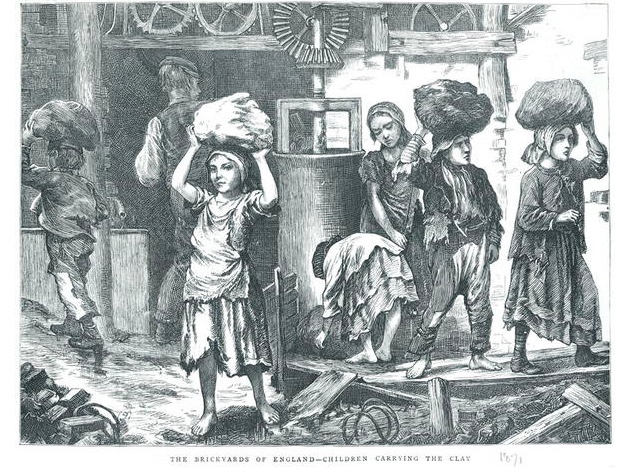

In 1940 Bowlby stated that the majority of children would suffer from some sort of anxiety during the war (Waugh et al, 2007, p.169). This may seem like an overly sweeping statement to an obvious period of distress, however this claim was made before vast evidence was collated regarding the level of social damage sustained by children during the war. An example given by Bob Holman describes the story of a woman who revealed that as a five year old, she had been stripped and abused a number of times by the two teenage sons of her foster parents. Others were touched by her foster father (Holman 1995, p.94). Children were often subjected to neglect, something that could cause psychological harm when detached from their parents. In some cases labour was put in place of education when schools could not provide class space. For a child, life was changing rapidly in what Parsons and Starns called the ‘greatest social upheaval in modern Britain’ (Waugh et al, 2007, p.169). These are all factors that explain why in Waugh’s survey that 57% of evacuees she interviewed suffered some sort of abuse (Waugh et al, 2007, p.172).

Reports of poor care for evacuees became frequent, this was undoubtedly down to the fact that no systematic screening took place to ensure these people were suitable foster parents (Waugh et al, 2007, p.169). One statistic that is frequently mentioned throughout the historiography of this topic is enuresis. Welshman states that in a survey it was found that children who were neglected or were subject to physical, sexual or psychological harm commonly wet the bed (Welshman, 2010, p.178). Holman acknowledges this factor and goes into further detail, stating that estimates of this problem have ranged from 4% to 33% of evacuees, Waugh also addresses this topic in similar fashion (Holman 1995, p.107. Waugh et al, 2007, p.166).

In sum, the gas mask works for the historian as a reflection of what it was like to be a child during WWII. In amongst a rapidly changing social climate children had to deal with foreign objects like these, only adding to their sense of disorientation. Psychological damage is unfortunately the dominating topic surrounding children of this era. Does this really surprise you?

Bibliography:

Holman, Bob. The Evacuation: A Very British Revolution. Oxford, England: Lion, 1995.

Tittmuss, R. M. Problems of Social Policy: History of 2nd World War. London: Longmans, 1950.

Venken, Machteld, and Maren Röger. “Growing up in the Shadow of the Second World War: European Perspectives.” European Review of History: Revue Européenne D’histoire 22 (2015): 199-220.

Waugh, Melinda J, Ian Robbins, Stephen Davies, and Janet Feigenbaum. “The Long-term Impact of War Experiences and Evacuation on People Who Were Children during World War Two.” Aging & Mental Health 11 (2007): 168-74.

Welshman, John. Churchill’s Children: The Evacuee Experience in Wartime Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Source:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/GyXWnFaXQcKPYdV0cL5kyQ (date accessed: 10/11/2016)

Online resource:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/53/a2050453.shtml (date accessed: 13/11/2016)

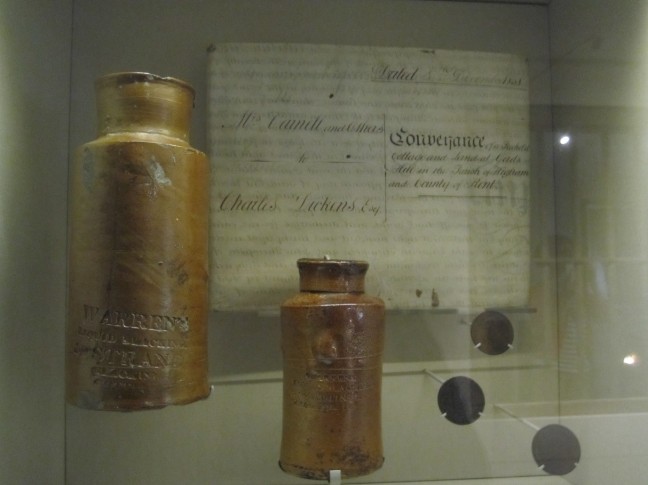

Bottles from Warren’s Blacking Factory where Charles Dickens worked in 1924. Held at the Charles

Bottles from Warren’s Blacking Factory where Charles Dickens worked in 1924. Held at the Charles